Tiers before tears: The three-tier model of intervention

Prevention is better than cure – A pupil-centred approach to holistic and academic support

“Children only get one childhood. They deserve to get the support they need to thrive and prepare for happy, healthy and productive adulthoods” (Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) and Alternative Provision (AP) Improvement Plan. HM Government, March 2023)

Anyone working in Education would agree wholeheartedly with the above statement. The question that keeps many of us up at night, though, is, ” So what does this support look like, and how can I implement it?”

In this think piece, I’d like to walk you through the three-tier model of intervention and support. I warmly invite you to join me as we unpack what each of the three tiers looks like and get into the (sometimes messy) business of flexing to this level of support in a system already burdened with overstretched resources.

What is the three-tier model of intervention?

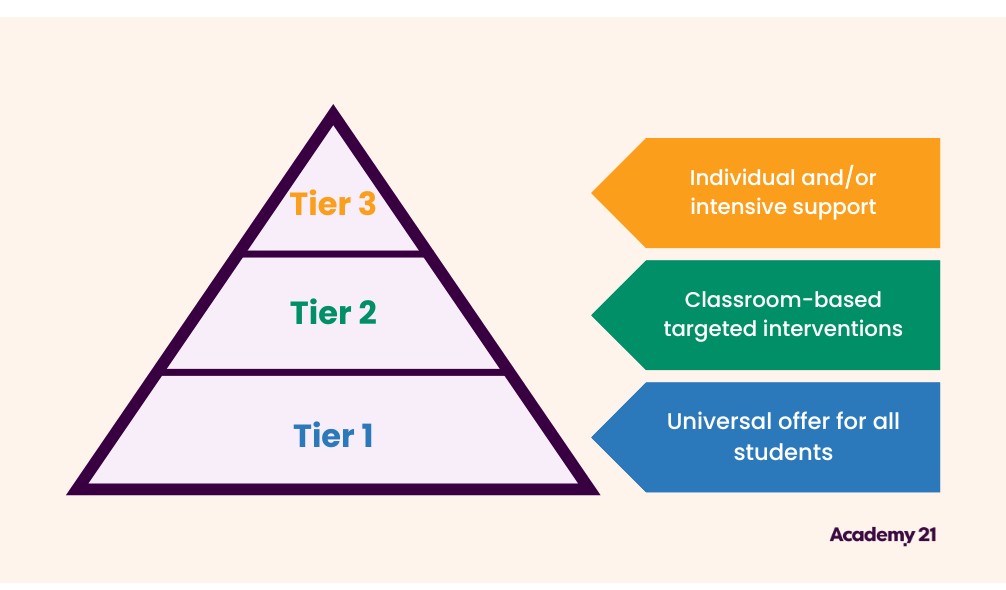

The notion of three tiers of support is not a new one. Whether we refer to them as ‘tiers’ or ‘waves’, the premise is the same; some pupils thrive under the universal offer that forms the fundamental pedagogy and practice in the mainstream classroom, whilst others need more targeted and sometimes individualised support. In the pictorial representation below, note the three tiers and what they refer to:

Let’s unpack some typical features at each tier when considering the support around the pupil.

Unpacking the three-tier model of intervention

Tier 1 – Universal offer for all pupils

Relational approach

The teacher takes a relational approach to ensure all pupils feel ‘seen’. This might be a personalised welcome, a reminder to include a previous feedback point in their next piece of work, or a word of encouragement when they find something tricky.

Scaffolding of tasks

At a universal level, this may look like a ‘menu’ of support pupils can self-select to help them achieve the lesson’s aims. For example, word mats, writing frames, success criteria, concrete resources to support their conceptual thinking, or ‘working walls’ to help them remember what has already been covered in a particular topic.

Clearly defined ‘aims’ or ‘learning objectives’

Clearly defined ‘aims’ or ‘learning objectives’, often with ‘success criteria’ hints for what to include. Providing these in written form reduces the pressure on auditory processing and memory. The core purpose is to ensure pupils don’t need to retain verbal instructions in their working memory, as they are listed on a board/paper somewhere for reference. We, therefore, free up space in their working memory to focus on the important business of learning. Strategies such as these are universal to all and seek to reduce cognitive load for pupils.

Tier 2 – Classroom-based targeted intervention

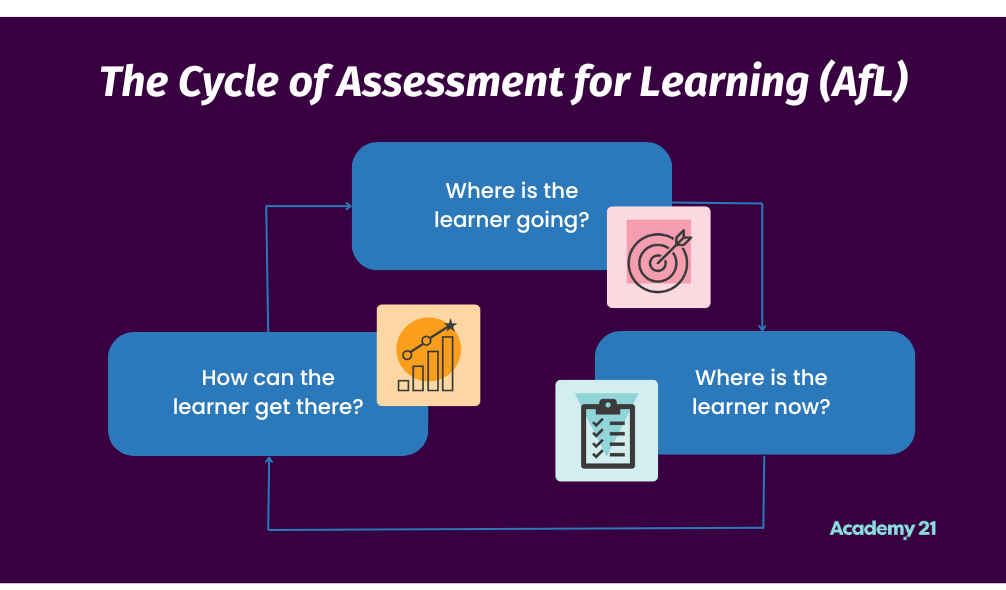

Assessment for Learning (AfL)

Assessment for Learning (AfL) is, for teachers, the ‘gift that keeps on giving’. When we are well-attuned to our pupils’ needs and constantly assess what concepts they have or have not entirely understood, we form a sense of those who are ready to move on and those who just require a little more support and/or consolidation.

Targeted and differentiated questioning

Through targeted and differentiated questioning, we can ensure we adapt our pitch and pace for different groups of learners. In practical terms, we might have one table of pupils who just need a little more modelling before being set off to complete independent work or another table that would benefit from using manipulatives to formulate their thinking about a particular mathematical concept.

Proactive support to ease the learning pace

Whilst Tier 2 support can be an ‘in the moment’ intervention, as outlined above, it can also be a tool we use to mitigate the risk of pupils finding the pitch and pace too fast during a lesson. For example, suppose we have a group of pupils for whom processing takes a little more time. In that case, we may direct them to a ‘pre-teach’ activity to familiarise them with the essential vocabulary or concepts discussed in the upcoming lesson.

This way, much like in Tier 1 scaffolding, we have sought to reduce the pressure on working memory and cognitive load by giving them helpful scaffolds beforehand that all work together to build on their existing schemas (complex neuronal pathways full of learning, concepts and links that are built over time and experience).

Adapting environments for sensory and behavioural needs

Where an additional need is pastoral, sensory or behavioural (rather than cognitive or academic), the approach to Tier 2 may be slightly more nuanced. For example, suppose we are working with a group of pupils who, for various reasons, find the ‘hustle and bustle’ of a mainstream classroom a little too overwhelming. In that case, we might schedule part of their learning in a low-arousal space, with less sensory input or fewer children to trigger their anxieties.

The cognitive and academic demands of the lesson may be the same but given the opportunity to attempt these in an environment more conducive to their needs, the progress made and the depth of learning achieved will be tangible and well worth the efforts made to accommodate these adjustments.

Tier 3 – Individual and/or intensive support

For some pupils, the mainstream classroom might be incompatible with their level of need. It’s important to note, though, that this might be a transient or time-limited difficulty. Some pupils may have a medical condition that means they are too unwell to be physically present in a school building. Still, they have the cognitive capacity (and often desire!) to continue with their studies while recovering.

Some pupils may have got themselves into a pattern of behaviour that self-perpetuates an underlying belief that they ‘can’t’ comply with rules or expectations. For pupils in patterns of repeat suspensions or isolations, this can be a complicated cycle to break, as its root is often low self-esteem or delayed trauma response.

A relational approach

This loops us back to the importance of a relational approach, where repeated positive adult-pupil interactions will enormously impact over time. The think-piece here is that it takes tremendous resilience and self-awareness from the adults working tirelessly with these pupils to ensure the repetition of interactions is consistent and positive.

If this is achieved, the neuronal pathways in the child/adolescent brain become stronger (through myelination), and ultimately, we witness a slow but steady shift towards self-belief, confidence, and trust in the adults around them.

When our pupils make this shift, they move from ‘fight/flight’ responses into a more measured response pattern, where their cortex (responsible for logic, reasoning, and thinking) is more easily accessible. In real terms, we see less impulsivity, less self-perpetuating negative behaviours, and more openness to learning and self-regulation.

Internal Alternative Provision

The above point can also be applied to pupils with anxiety or other mental health challenges that make crossing the threshold of a mainstream site feel like an impossible task. Emotionally Based School Avoidance (ESBA) can feel incredibly isolating for young people and their families and can often leave school staff feeling unsure of how to support them. That’s where an open-minded approach to suitable interventions (often time-limited) can be particularly beneficial.

This may be called an ‘Internal Alternative Provision’ or IAP for particular groups of pupils or settings. It would typically be an on-site space that can accommodate academic learning but with an alternative approach. Usually, IAPs have a holistic approach that addresses social, emotional, and behavioural needs in parallel to the educational curriculum.

The ‘diet’ a pupil receives in such provision can be an excellent springboard for preparing them for full student reintegration after small-group and intensive intervention. However, this approach is not without its challenges.

Budget constraints mean IAPs can be challenging to staff with subject specialists (secondary) or qualified teachers (primary and secondary) in many settings. The pastoral skillset needs to be considered within this type of provision, and a growing body of research tells us that pupils in IAPs benefit enormously from trauma-informed, relational approaches with adults who are well-versed in working alongside our young people through an empathic and patient lens.

It’s important to note that if we get the latter right, we can provide academic learning via creative approaches that do not require additional teacher recruitment, which is rarely feasible within existing budgets.

The role of online education

This is where online education, particularly online Alternative Provision, can play a vital role, all whilst pupils are accessing onsite IAPs. Their curriculum can be delivered at age and stage-appropriate levels, right through to GCSE, by qualified and subject-expert teachers under the physical supervision of their trusted support staff.

A ‘circuit break’ approach can be the optimum solution for some of our most complex pupils. Time away from the environment they have been so accustomed to ‘failing’ in can give them the space and privacy to reflect on and act on what they are academically capable of. This is a space where online learning can really benefit both the pupil and the school, which has exhausted all other means of intervention.

In Tier 3, it is easy for leaders to fall into the trap of thinking of a move to online learning as a ‘failure’ or as a ‘destination’ that they do not want for their students. At Academy 21, we really emphasise that online learning in this way is an intervention, not a destination.

Whether the pupil successfully reintegrates into their previous mainstream or transitions into a more suitable onsite setting, the measure of success for us is that we have been able to act as the educational bridge between those two periods of time. We pride ourselves on our relational approach and the emphasis on those building blocks of self-esteem that mean even the quietest, most disengaged learners eventually begin to interact in our lessons and converse with their teachers.

Sometimes, the anonymity of a screen is precisely what they need to make that first brave move, and our teachers are highly adept at building on those interactions and participations little by little until we have pupils who are enthusiastic and steady enough to start reintegrating into onsite education again.

Tim Fargo once said, “Until you cross the bridge of your insecurities, you can’t begin to explore your possibilities”.

In the context of a tiered approach to intervention, this applies to individual pupils and the school leaders who serve them. At Academy 21, we’re here to help you take that first step onto the bridge.